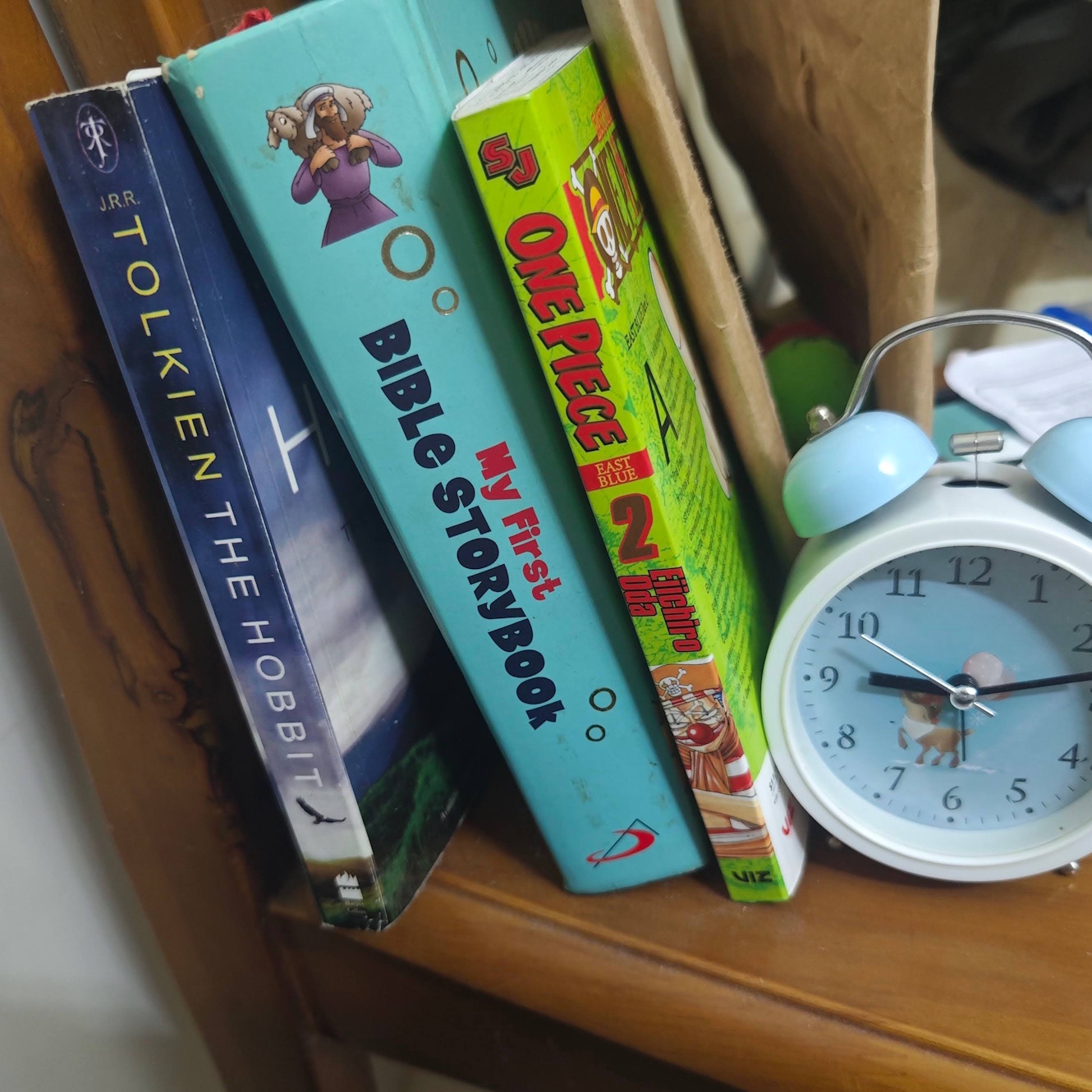

Last night, after we had finished our nightly routine of a Wordle game (the word was ‘spear’ in five tries), I asked Max what he had learnt in school that day. He said he had read The Open Window by Saki (H.H. Munro) in his English class.

‘Appa, I’ll tell you the story,’ he declared, grinning at the unexpected role reversal. Usually, it was the other way around.

‘Do you know the story, Appa?’ he asked. I admitted that I might have read it but couldn’t recall the details.

As he began narrating, fragments of the story resurfaced in my mind. I had read this story. I must have been his age—maybe a little older. But there it was, coming back in fragments.

When he finished, he remarked that he liked the last sentence: Romance was her speciality. Then he added, ‘Appa, did you know “romance” can also mean a fantasy story?’

With my memory fully refreshed, I gently corrected him: ‘Actually, the last line is Romance at short notice was her speciality.’

Max blinked, then nodded. ‘Oh! Now I remember’.

And just like that, he was done, stretching out under the covers, already halfway to sleep. But I wasn’t.

Memory is strange. I can forget what I did five minutes ago, but a story I read decades back? That lingers. Maybe if I wrote my to-do lists as stories, I’d actually remember them.

After he had gone to sleep, I lay there, thinking about that last line. What could I do with it?

And then it struck me—perhaps I, too, could practise romance at short notice.

I could write vignettes. Short, sharp stories, woven from fleeting moments, laced with memory and meaning.

And so I did.