After nearly 50 weeks, it’s time for me to close my career break and re-enter the familiar highs and lows of full-time work.

I went into the break imagining long, uninterrupted silence. I expected the solitude. I didn’t expect to miss talking to people as much as I did. For someone who sits slightly on the introverted side of things, it was a surprise to realise how much my mind depends on conversation—on that small spark that jumps between people when the right question is asked. It was also one of the reasons I felt ready to return. I’m in the prime years of my working life, and I want to spend them immersed in collaboration rather than orbiting it from a distance.

During the break, I found myself rethinking the work of a technical writer in a year filled with noise, speculation, and small pockets of clarity. I now think of technical writing as something shaped by humans and machines, each with their own strengths. I had a chance to talk through those early thoughts and write a little about them.

This was also a year of watching the fear and confusion around technical writing and AI. My view remains simple: AI is a tool. Useful when used well, unhelpful when not. I saved time with it, then spent twice as much trying to make it understand what I wanted. Strangely, I was more patient with the machine than with humans. I’m still thinking about what that says. It was a reminder that tools change—but the craft, and the expectations around it, still need human judgment.

Somewhere in all this, I finally learned to relax without guilt—a life skill I wish someone had taught me much earlier. I made space to feel the sting of rejected applications without letting it define me. That discomfort became a quiet tutor, nudging me to reassess what a technical writer really does and what kind of writer I want to be.

I let myself chase ideas without a roadmap. I vibe-coded whenever something caught my attention or when a small itch needed scratching. I built a Readest-to-Readwise highlights importer, a LinkedIn carousel builder that uses Markdown, and a Google Sheets–to–JSON converter to clean up my book library.

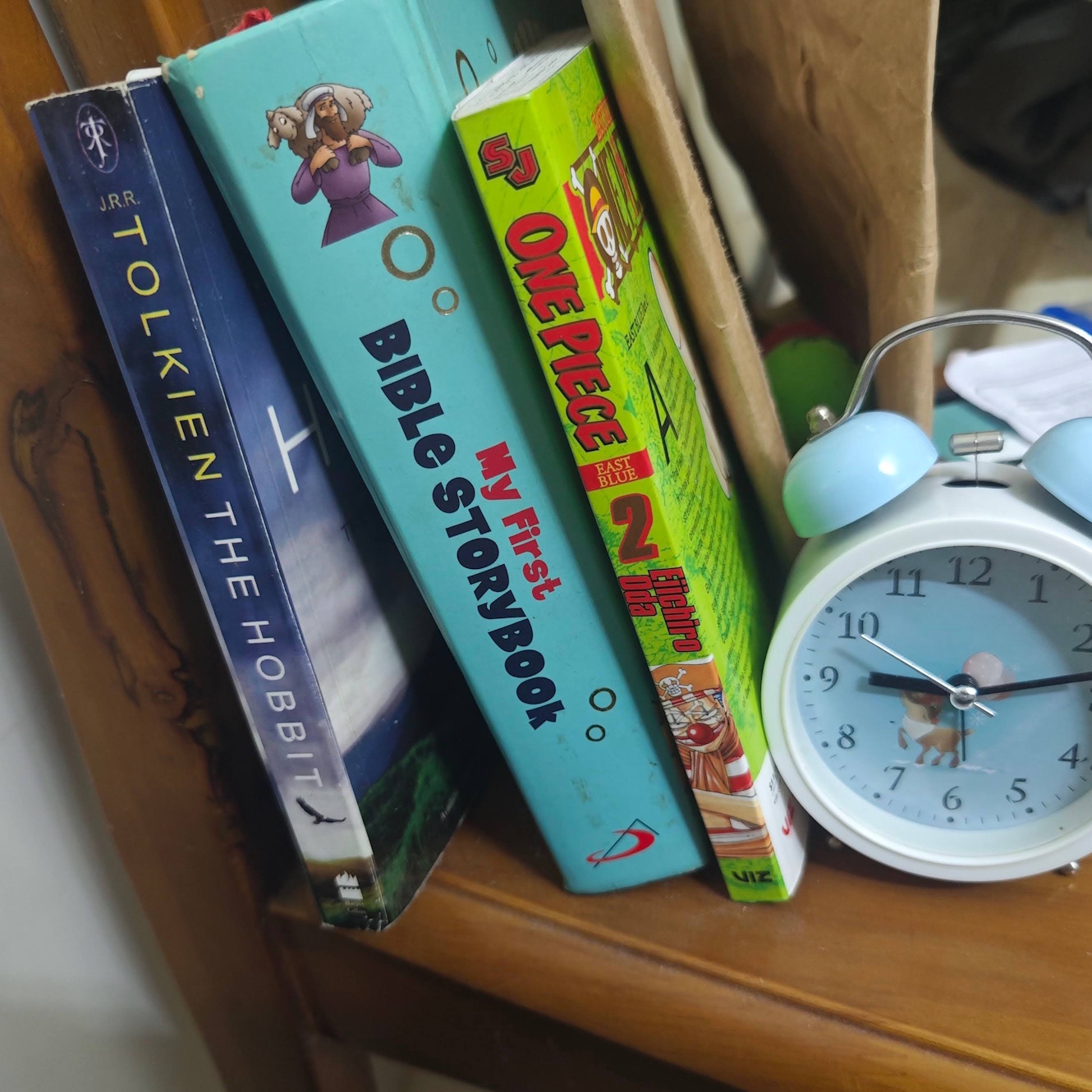

I read a lot of books in my yearly pursuit of a hundred, and an unreasonable number of web novels—mostly in the litrpg and xianxia genres. I binge-watched K-dramas and anime, and at 1.7× speed, discovered that Japanese sounds strangely soothing and mellifluous to my ear in a way Korean doesn’t. A highly specific discovery, but a delightful one.

And on some mornings, I took post-breakfast naps, the kind of indulgence that only makes sense when you have nowhere urgent to be. Somehow, the post-lunch siesta never caught on.

All of this taught me to let life unfold without forcing it. It reminded me that being a small fish in a big pond is often the healthiest, happiest place to grow. It quieted that background hum of “What next?” that had shadowed me for months.

Now, as I return to work, I’m stepping in with clearer intent, grounded expectations, and a renewed respect for the simple act of showing up, connecting, and doing the work with others.